“That whole album is so pure. I love that music. I love that

old feeling of just the music. Nothing else mattered to us then… There was no

success, nothing to live up to, just love and music and life and youth. That

was a happy time. That is Crazy Horse.” – Neil Young in 2012

While his first solo album was a bit of a muddle with Young working with two producers and musicians such as Ry Cooder who were not wholly sympathetic to the music being recorded, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere succeeds in all places where Neil Young stumbled or failed. For the first time, Young’s music erupts from the speakers with all the power that they required. The album was a perfect alignment of inspired songwriting, simple but effective production care of David Briggs and the introduction of one of the best bands ever committed to tape: Crazy Horse.

While his first solo album was a bit of a muddle with Young working with two producers and musicians such as Ry Cooder who were not wholly sympathetic to the music being recorded, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere succeeds in all places where Neil Young stumbled or failed. For the first time, Young’s music erupts from the speakers with all the power that they required. The album was a perfect alignment of inspired songwriting, simple but effective production care of David Briggs and the introduction of one of the best bands ever committed to tape: Crazy Horse.

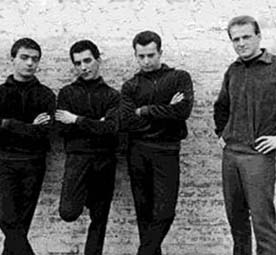

At this time, Crazy Horse consisted of Danny Whitten, Billy

Talbot and Ralph Molina on guitar, bass and drums respectively. Young had come

across their main band, The Rockets, in Los Angeles and fell in love with their

sound. The Rockets had evolved from Whitten’s group Danny and the Memories,

pictured above, who performed doo-wop a cappella. Danny and the Memories

released one single (and recorded one that was never released) in the

early-to-mid 60s before morphing into a group called The Psyrcle in 1965. The

Psyrcle recorded a single for Autumn Records produced by Sly Stone but

unfortunately, after it was pressed, the band decided to shelve it. A recording

of The Psyrcle performing a cover of “Land of 1000 Dances” for the Scopitone

film jukebox system (though Young attributes this to Danny and the Memories

which seems more likely given the style of music and dress) along with links to

videos of the Danny and the Memories’ single “Can’t Help Lovin’ That Girl of

Mine” and its B-side “Don’t Go” are available on this website devoted to Whitten.

After witnessing a live performance by The Byrds (who of

course featured David Crosby at this point), they decided to change direction

and become more focussed on rock. They expanded their line-up to include the

Whitsell brothers (George and Leon) on guitars and Bobby Notkoff on violin,

then they took on the (far better) name of The Rockets. Although they were not

entirely happy with the recording, The Rockets still showed plenty of potential

on their self-titled debut. Their fusion of the West Coast melodic sensibility

and psychedelia with a nod to R&B along with buckets of attitude shines

through even today, especially on explosive tracks like “Pills Blues” and Whitten’s

“Let Me Go” (just listen to Notkoff’s amplified violin solo, a Californian twist

on John Cale’s austere viola with The Velvet Underground if ever I heard it):

Still in Buffalo Springfield and seeing The Rockets tear it

up on stage, Young had a similar experience as those from The Psyrcle did when

they saw The Byrds. He realised that these guys were the sort of musicians he

wanted to work with. Young eventually befriended the group and ended up playing

with them on stage at The Whiskey A Go-Go and back at their house in Laurel

Canyon. He got on particularly well with Whitten, Talbot and Molina, so Young invited

them to jam on his own music at his home Topanga. Around the time Neil Young

was released, Young and Crazy Horse (as they were now christened) were already

sowing the seeds of Everybody Knows This

Is Nowhere: “…that’s when we first played “Down by the River” and “Cinnamon

Girl”. It felt really good,” said Talbot while reminiscing about the early days

of Crazy Horse in an interview with Barry Alfonso.

Those two songs had a magic about them from the beginning. They hook into the ear and will not get out no matter what. This is not that surprising considering Young wrote them while running a fever of 103 °F (that’s 39.4 °C for us Europeans). “I had been sick with the flu, holed up in bed in the house… I was delirious half the time and had an odd metallic taste in my mouth. It was peculiar. At the height of this sickness, I felt pretty high in a strange way. I had a guitar near the bed… I took it out and started playing.” This flu-fuelled guitar playing resulted in “Cinnamon Girl” before Young ended up jamming along to the radio. According to his memoirs, it might have been “Sunny” by Bobby Hebb:

Those two songs had a magic about them from the beginning. They hook into the ear and will not get out no matter what. This is not that surprising considering Young wrote them while running a fever of 103 °F (that’s 39.4 °C for us Europeans). “I had been sick with the flu, holed up in bed in the house… I was delirious half the time and had an odd metallic taste in my mouth. It was peculiar. At the height of this sickness, I felt pretty high in a strange way. I had a guitar near the bed… I took it out and started playing.” This flu-fuelled guitar playing resulted in “Cinnamon Girl” before Young ended up jamming along to the radio. According to his memoirs, it might have been “Sunny” by Bobby Hebb:

The stabbing rhythm of the guitar mixing with Young’s

sickness-induced high morphed into one of the great guitar songs. “Down by the

River” bears only the barest resemblance to “Sunny”; aside from being mildly R&B

orientated it has an entirely different feel to Hebb’s song. Feeling in the

zone, Young also wrote “Cowgirl in the Sand” on this day which must hold the

record for one of the most productive bouts of influenza in musical history!

All three songs use repetition and slight variations in a way that is

reminiscent of a fever dream. The guitars reiterate the same chords over and

over again, never fully breaking free of the riff. Luckily, unlike a fevered

condition, these songs are not distressing or unsettling. They are like old friends,

familiar and welcoming.

The repeating riffs provided a backbone for some of Young’s most incendiary guitar playing at the time (though I would argue he has surpassed himself on many occasions since). Part of this was due to him finding a band that would give him the space to explore the fretboard and, by extension, his musical whims and part of it was due to him coming across an old electric guitar with tons of character. Old Black was a 1953 Gibson Les Paul Custom that was originally gold but repainted by a previous owner. It roared like a mythological beast in Young’s hands (“It sounded like hell. Neil loved it,” remembered Jim Messina, who was the owner previous to Young). Combined with a similarly boisterous Fender Deluxe amp, Young had previously used it on a wonderful little song called “Houses” by Elyse Weinberg (recorded by Briggs and included below) but it really came to life when the Horse got involved, Young and Whitten bouncing off each other and driving each other onwards and upwards. To not get lost in the endless guitar heaven of “Down by the River” or “Cowgirl in the Sand” is to be dead.

The repeating riffs provided a backbone for some of Young’s most incendiary guitar playing at the time (though I would argue he has surpassed himself on many occasions since). Part of this was due to him finding a band that would give him the space to explore the fretboard and, by extension, his musical whims and part of it was due to him coming across an old electric guitar with tons of character. Old Black was a 1953 Gibson Les Paul Custom that was originally gold but repainted by a previous owner. It roared like a mythological beast in Young’s hands (“It sounded like hell. Neil loved it,” remembered Jim Messina, who was the owner previous to Young). Combined with a similarly boisterous Fender Deluxe amp, Young had previously used it on a wonderful little song called “Houses” by Elyse Weinberg (recorded by Briggs and included below) but it really came to life when the Horse got involved, Young and Whitten bouncing off each other and driving each other onwards and upwards. To not get lost in the endless guitar heaven of “Down by the River” or “Cowgirl in the Sand” is to be dead.

The album was recorded in January and February 1969, a month after the release of Young’s solo album. Recording did not take long, it looks longer on paper due to the fact that Young took his leave in the middle of the sessions to do a solo tour in support of Neil Young. This time, everything was recorded live with the band playing together in the same room. The change in feeling on these recordings is palpable, even over 40 years on (and if you ever had the mind-numbing experience of recording track by track and then going back to jamming out naturally, this makes total sense). There is a grittiness that runs through the songs that makes them sound more honest and real than those on Neil Young; Reprise Records, recognising that this was a rougher album than its predecessor, even created a promotional item in the form of a bag of Topanga Canyon dirt! Regrettably, this is the only full studio album featuring the original line up of Crazy Horse (though they would contribute to individual songs on After the Gold Rush and record a self-titled album of their own) and while the charge running through the music was still there in Crazy Horse Mk. II, the loss of Whitten to an overdose of Valium and alcohol in 1972 makes these sessions particularly poignant.

Although not to the same extent as his debut album, Young has some regrets about Everybody Knows This Is Nowehere. According to Waging Heavy Peace, there is another version of “Cinnamon Girl” to be released on a future Crazy Horse compilation (Early Daze) where Whitten (and not Young sings) the high part. Young feels that he made the wrong decision by including the version that is on the album as it stands (“Danny, so fucking great… He was so special, he was like a real force… There’s nothing about him singing with me that’s like a backup singer”). Unfortunately, there is no official live release with Whitten singing “Cinnamon Girl” to compare but based on the Live at the Fillmore East disc from Archives Volume One, Whitten could hold his own against Young. This is of course not news to anyone who has heard Crazy Horse’s self-titled album from 1971 where any accusations of Crazy Horse being a loose or sloppy band fall short.Whitten’s early death is another of those “might have been” situations: maybe he might have gotten clean, maybe he might have recorded another great Crazy Horse album (and another and another), maybe Young would have taken a different artistic path than the one he did (as Whitten’s death echoed for years in Young’s music). We will never know.

We will also never know what would have happened if The Rockets had been allowed to develop at their own pace without Young cherry picking half the band. Although history suggests that Crazy Horse were only ever intended as a temporary thing, the fact that the subtitle of “Running Dry” is “Requiem for The Rockets” could not have bode well for the future of the group back in 1969. However, The Rockets’ album was not selling well and was poorly promoted by their label White Whale. It did not help that they blew one of their only radio appearances by swearing themselves off air and out of the studio. In the endless road metaphors that follow Young's music around, The Rockets unfortunately hit a dead end and had no reverse gear. (I never said it would be a good metaphor.)

Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere has stood the test of time far better than its predecessor though it only marked the beginning of a fruitful if difficult decade for Young and Crazy Horse. Despite being essentially his dream band, he would leave them in the stable more often than not. While a part of me thinks this was a pity, it is clear from Young’s back catalogue that for his own sake, he needs to shake things up constantly. And with After the Gold Rush, he would change direction yet again but that story is saved for next time.

Cover image taken from the Discogs entry for the original 1969 US pressing of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (accessed 8th January 2013). Danny and the Memories photo taken from www.dannyraywhitten.com (accessed 9th January 2013). Billy Talbot quote from the liner notes to Crazy Horse’s The Complete Reprise Recordings 1971-’73 (2005). Neil Young quotes from Waging Heavy Peace by Neil Young (2012), “Archives Review Session, Broken Arrow Ranch, February 24, 1997” video file found on Archives Volume One (Blu-ray; 2009); see disc 4 Topanga 2 (1969-1970). Jim Messina quote from Shakey by Jimmy McDonough (2003). Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere is available on Reprise Records on CD, HDCD and LP.

I have never heard that Danny Whitten died from a mixture of Valium and alcohol, what is your source for this? I have only ever read that his death was due to heroin.

ReplyDeleteHi Greg. I had heard the story about heroin too from multiple sources but in the liner notes to The Rockets CD reissue, Whitten's sister states that the coroner's report did not report high levels of heroin in his blood but that there was enough Valium and alcohol to have caused an overdose. It could be Whitten's sister trying to save face but considering his heroin addiction was well known and documented, I find that idea unlikely.

ReplyDeleteHmmm, interesting. I wonder how the other principles in Danny's life view this version, given their seeming unanimous acceptance of the heroin story. It would be interesting to get a comment from the remaining CH members, given the liner note you cite. In any event, your Valium and alcohol assertion made me wonder about those last few hours of Danny's life, how he got himself together enough to even make the flight back to LA, how he must have appeared to the other people on the flight given the state he must have been in, whether or not anyone is on record as having interacted with him back in LA just before his death. Very sad to think of, the pain and misery he must have been in.

ReplyDeleteIt's all in "Shakey":

DeleteOn the flight back to Los Angeles, Whitten reportedly became inebriated and had to be restrained. Later that same day—November 18, 1972—he wound up at a friend’s house at 143 North Manhattan Place. That evening, Whitten called up Nitzsche. “Danny asked, ‘Would you be there for me? No matter what?’ I said, ‘Sure,’ and he said, ‘That’s all I wanna know,’ and hung up.” At some point, Whitten went into the bathroom and never came out. A female companion found him dead on the floor. An autopsy revealed that he had died of “acute diazepam and ethanol intoxication”—an overdose of alcohol and Valium.

“I always thought that was kind of ironic, ’cause Danny more or less taught me about drugs, and he’d always tell me not to take depressants when you’re drinkin’,” recalled childhood friend Larry Lear. “He was real explicit with that.” Some say Danny’s death was just one of those unfortunate accidents, while others, like Jack Nitzsche, believe it was suicide: “The third day Danny was up at the ranch, he said, ‘I got a feeling Neil’s gonna fire me. Man, if that happens, it’s all over for me. That’s just the end of the line.’ The poor fucker.”